A HAUNTED BOTANY

Beyond colonial ways of being and knowing.

Overview

“Our aim is to frame the multiple sides of a trade route, holding in tension the ways disparate geographies continue to impact and inform each other centuries later.”

— Gwyneth Shanks & AB Brown

Co-created by AB Brown and Gwyneth Shanks, a haunted botany is a multi-sited, socially engaged performance and printmaking project that explores the colonial entanglements of plants, people, and place. An ongoing series, a haunted botany was first performed in 2023 at the Hudson River Park in Manhattan. That initial performance focused on the logwood plant. Subsequent performances at the Maine Maritime Museum in Bath, Maine and at the Arnold Arboretum of Harvard University in Boston, Massachusetts focused on Eastern White Pine.

In this multi-year project, Brown and Shanks recreate to scale the seventeen sails that were rigged on colonial-era tall ships. The sails are treated with cyanotype dye, used in the

Histories

As a young man, Joseph Banks

served as the botanist for Captain James Cook’s 1768-1771 voyage of the HMS Endeavor to Brazil, Tahiti, New Zealand, and Australia. Banks kept a detailed diary, describing what he collected and also how he preserved various plant specimens. Throughout these long sea voyages, sailors would need to make continued repairs to the sails; often, when the HMS Endeavor would drop anchor close to shore, sailors would row the sails to land and spread them out on the beach, better to see the repair work needed and communally sew rips and tears. Banks, taking note of this practice, realized the spread-out sails would serve as an ideal ground for drying the various plant specimens he was collecting.

Samuel Atkins (1787-1808), HMS Endeavour off the coast of New Holland, 1794.

The diary anecdote, describing his process for laying out and drying the plants, captivated Brown and Shanks’ visual imaginary. Here was a moment in which the technology (sails) needed for imperial expansion quite literally made material contact with the central driver of that expansion, plants. Banks’ act revealed the deep connections between botany, imperial wealth, geopolitics, human intimacies, and contemporary instances of violent subjugation indebted to these histories.

Thomas Phillips, Portrait of Sir Joseph Banks, as president of the Royal Society, 1812.

original process for making blueprints, to create large scale sun prints of archival objects, texts, and images that reveal a plant’s colonial histories and the ways they continue to imprint the present. The final cyanotype prints then serve as sites for public programs, like storytelling focused on participants’ relationships to a given plant’s history, lectures, and workshops. Across these formats, programs explore how botany’s colonial legacies live on through our everyday relationships to the environment, the increasing effects of climate change, and the policies that result in environmental racism, healthcare injustice, food insecurity, and more.

Ongoing support for a haunted botany is provided by the Buck Lab for Climate and Environment.

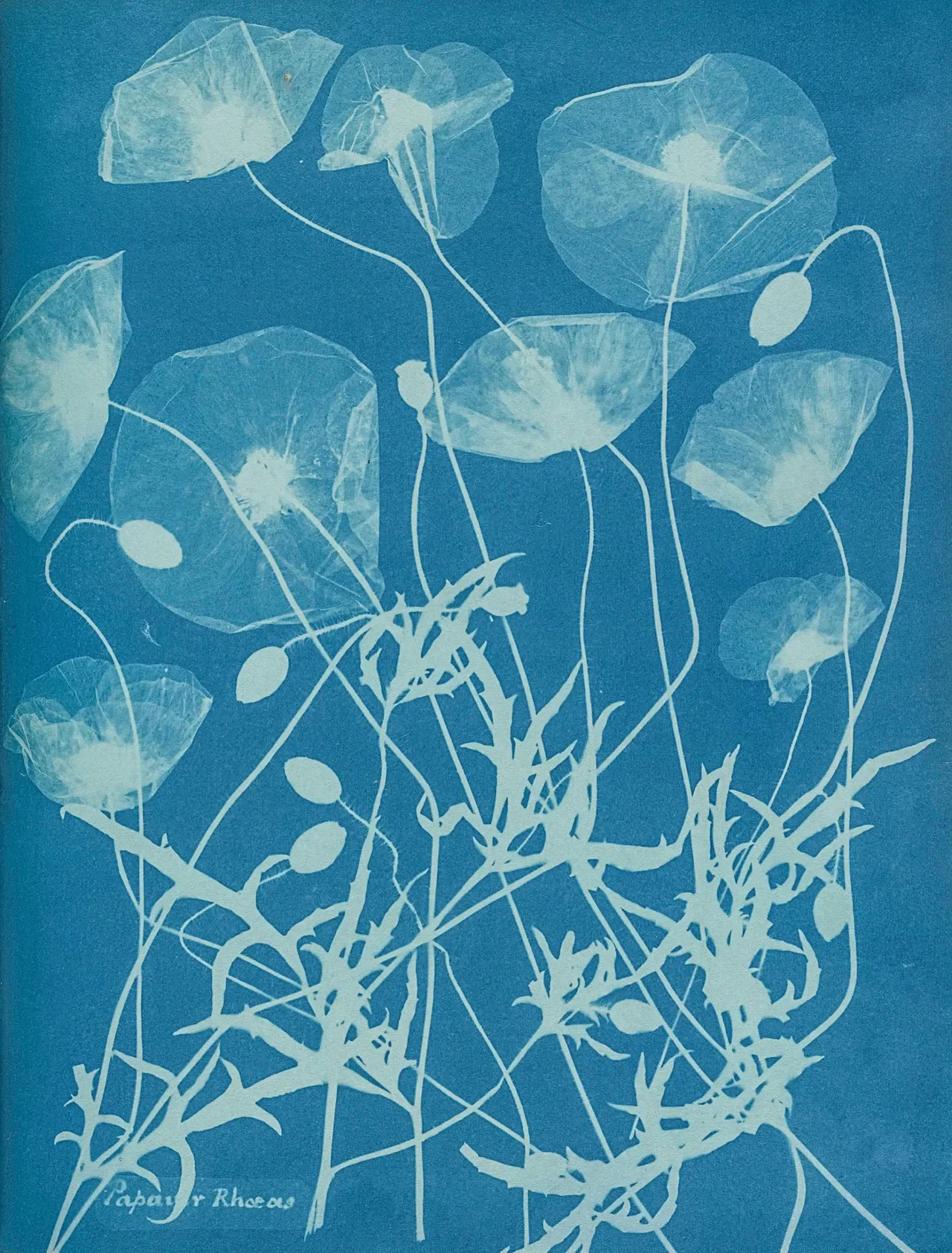

It also reveals the profound precarity of colonial endeavors—the constantly ripped sails, torn in high winds, and delicate plant specimens, always already on the verge of crumbling and decaying once gathered. As the artists imagined a topsail spread flat, covered in neat rows of drying plants, the image reminded them of the most common of cyanotype prints—perfectly pressed white outlines of leaves and petals against a Prussian blue background.

Cyanotype was invented by the British astronomer and inventor John Herschel in 1842, following a four-year stint in colonized South Africa. While there, amongst other pursuits, he and Margaret, his wife, created nearly 150 botanical illustrations of indigenous flora. This fascination with plants and the forms colonial botany took—the botanical illustration—no doubt informed many of Herschel’s own experiments with cyanotype, creating a body of work that tied the early proto-photographic process to the capture of vegetal detail. Figures like Anna Atkins (a family friend of the Herschel’s) popularized the utility of cyanotype for botanists—amateur and professional alike. Cyanotype was also the original process for creating and reproducing architectural drawings. Replaced in the 1940s by faster processes, architectural plans still bear the traces of their cyanotype lineage: the blueprint.

Photograph by Anna Atkins and Anne Dixon; courtesy Hans P. Kraus, Jr., New York

While in use, sails are buffeted by rain and debris, leaving imprints on the fabric. In other words, the act of sailing itself becomes a kind of print-making process in which supra-human and supra-geographic records of a ship’s encounters are left behind. As technologies that helped propel colonization, these properties of sails became an organizing metaphor: as unintended records of sorts, they transform the fixity of textual claims into colonial residues that linger into the present. Likewise, cyanotype’s history as a process through which to create and reproduce architectural plans (including of ships) seemed to the artists to usefully and poetically align with the ways botany as an emergent scientific discourse and colonial governance sought to create hierarchical and reproducible structures of control, ordering, and differentiation.

In distinction to this, cyanotype, as a print-making process, is unpredictable. Contingent upon the environment—sunlight, shade, and shadows—its results are difficult to control, slow, and fix.

Resulting cyanotype sail print produced during the June 2023 Hudson River Park performance, focused on logwood.

In a haunted botany, Brown and Shanks forward performance-based printmaking as an anti-colonial method. Cyanotype’s material and chemical properties offers a resistant practice for confronting the scope and scale of coloniality. Their use of cyanotype frames these histories as blueprints for making sense of our present while also suggesting fugitive practices that might exceed the impacts settler colonial violence has wrought on the environment, geopolitical formations, and communities. a haunted botany imagines ways that, together, we might transform colonial infrastructures through refusing fixity and embracing processes of change. Through creating the cyanotype sails and then hosting conversations on them, objects’ imprints become sites for imagining otherwise the ways histories impact our present.

—AB Brown & Gwyneth Shanks

Performance still from a haunted botany: a performance for a forgotten forest, Maine Maritime Museum, Bath, Maine. May 17, 2025. Left to right: zavé martohardjono, Xinyi Zhang, Gwyneth Shanks, Galle, AB Brown, Yanira Castro, mayfield brooks. Photo credit: Kari Herer.