a haunted botany: a performance for a fugitive dye

Hudson River Park, Manhattan July 15, 2023 Sunny, hazy day with a high of 92 °F

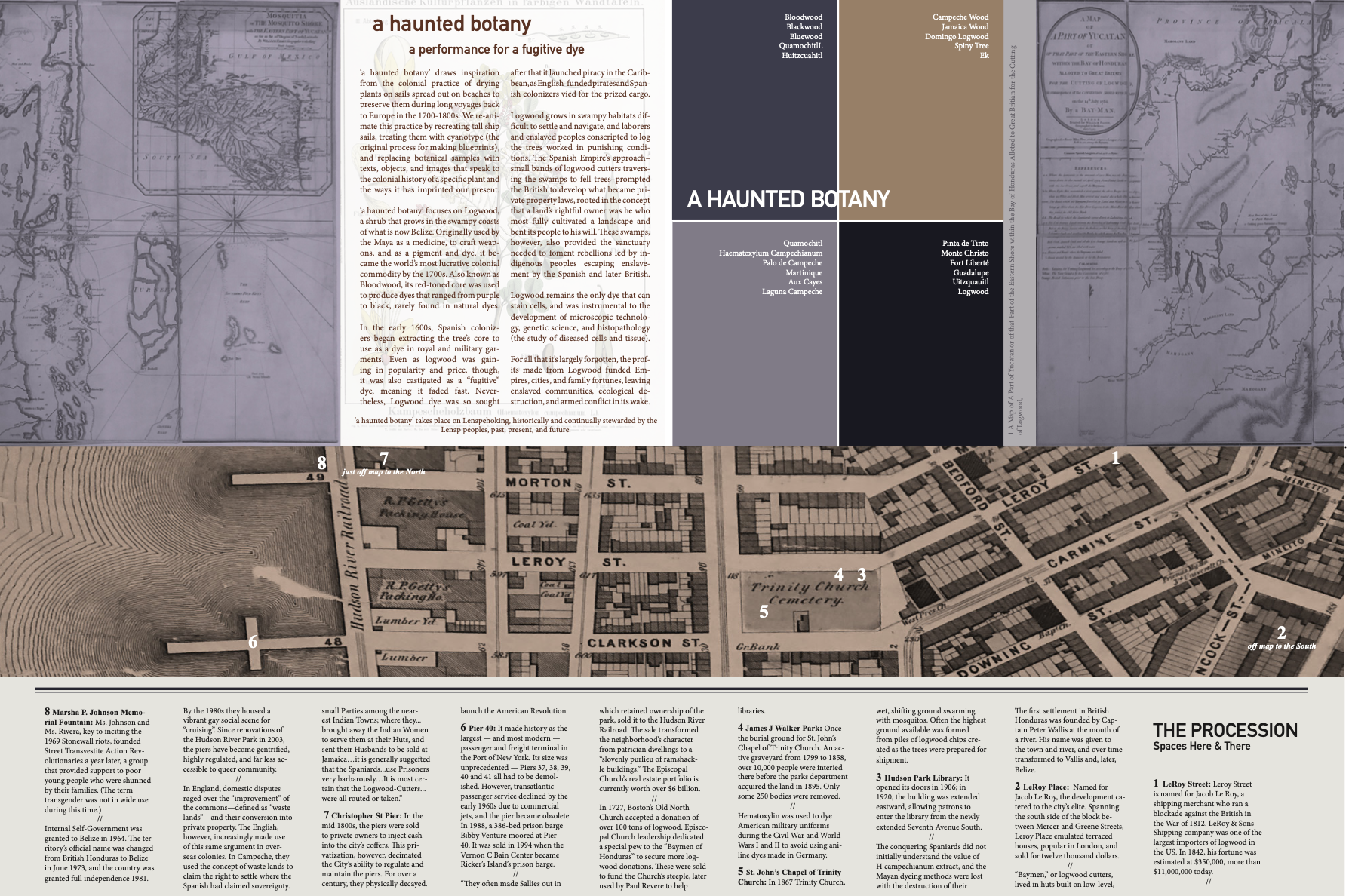

a haunted botany: a performance for a fugitive dye took place at Hudson River Park, and focused on Logwood, a coastal swamp tree that grows in what was, in the 1600s, known as Campeche—now Belize.

Once used by the Maya for medicine, weapons, and pigment, the tree’s red-toned core became a prized source of purple and black dyes—colors rare in nature and highly valued in European textile production. By the 1700s, logwood was the most lucrative colonial commodity in the world. Logwood’s extraction relied on enslaved and indentured laborers forced to work in brutal swamp conditions—terrains that also served as sites of resistance and refuge. The British used control over these landscapes to justify new systems of private property, linking land ownership to domination.

Hudson River Park is located where the city’s extensive 18th and 19th century finger piers once were. The performance was staged adjacent to the now extinct pier 48, owned in the early 1800s by the shipping company, Jacob LeRoy & Sons. LeRoy senior had made his fortune largely off of importing and exporting logwood, and the nearby LeRoy Street was named after him.

The performance began with a twenty-minute procession down LeRoy Street. The walk served as a performed geographic palimpsest, extant landmarks and buildings linked, affectively and poetically, to the ways the material conditions of Campache appear in archival records, which, of course, leave much out. The performance itself, which lasted a little under an hour, was largely defined by the stillness of simply waiting for the cyanotype to expose. On one side of the sail, the arrangement of archival facsimiles and objects attempted to reveal the contours of each in legible ways. On the other side, the arrangement placed objects in clusters—or glyphs—so as to transform the clarity of each objects’ use.

Near the end of the performance, performers approached each audience member and placed a handful of logwood chips in their hands, inviting them to place the chips in a pile on the sail. As, one-by-one, the sixty odd people deposited their logwood on the sail, a metal wedge used to split and fell logs, was slowly buried. As people walked back to their seats on the grassy lawn, their palms were stained red.

Collaborators

Performed by AB Brown, zavé martohardjono, Gwyneth Shanks, Peter Simensky, Khadija Travers, and Lu Yim

Costumes by Gwyneth Shanks

Program by AB Brown & Gwyneth Shanks

Photography by Auden Barbour

Videography by T Stricker

Video editing by Ezra Rose

Sail Fabrication by Doyle Sail Loft

Research Assistant Xinyi Zhang

Funding provided by the MAP Fund

Histories

Logwood, or Haematoxylum

campechianum is a scrappy tree that grows in the swampy coasts of what is now Belize, known as Campeche in the 17th and 18th centuries. Originally used by the Maya as a medicine, weapon, and to produce pigments and textile dye, it became the most lucrative colonial commodity in the world by the 1700s. Also known as Bloodwood, its red-toned core was used to produce dyes that ranged from purple to black, colors, which up until that point had been incredibly labor-intensive and expensive to produce.

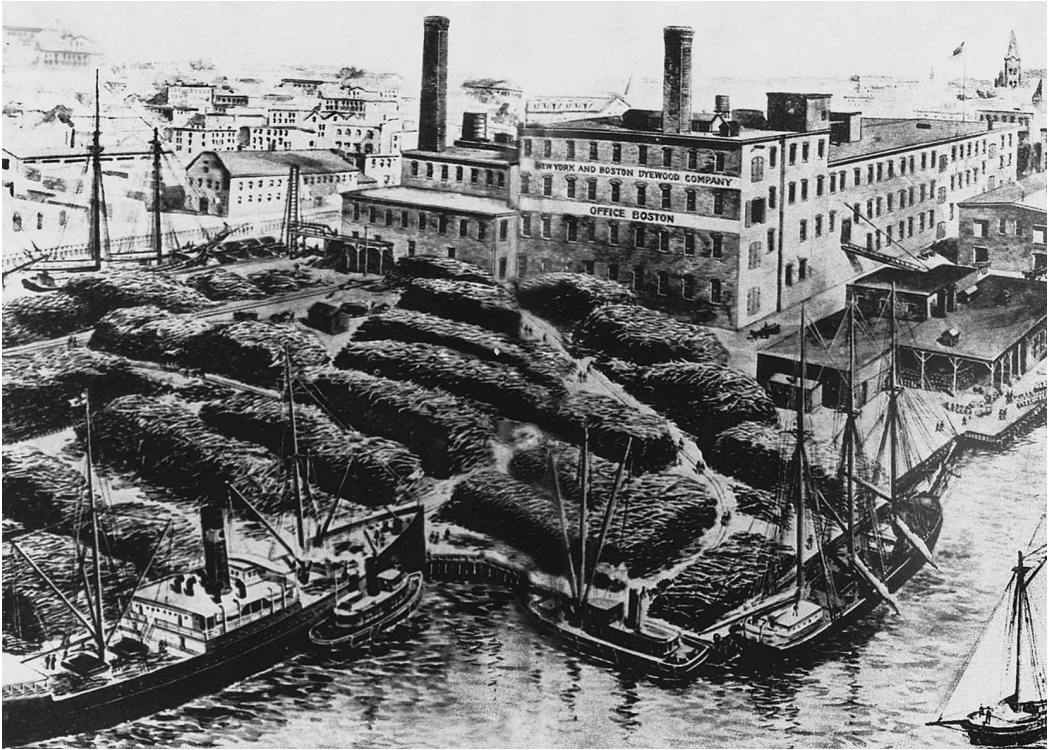

By the early 1600s, Spanish colonizers realized logwood’s dyeing properties and began logging the tree to use as a dye in royal and military garments. Even as logwood was gaining in popularity and price, it was castigated in some quarters as a “fugitive” dye, meaning materials dyed with it faded fast, vibrant purples and blacks shifting to lavender or light gray. Queen Elizabeth I outlawed the importation of logwood under severe penalties, a measure thought to be less about quality control than attempting to stymie the wealth Spain was accruing through logwood importation into Europe. Logwood remained highly desirable and even more so when, in the mid-1700s, European dye specialists figured out mordant recipes that rendered it dye-fast. The wealth to be made off of logwood contributed to the upswell in piracy in the Caribbean, as English-funded pirates and Spanish colonizers vied for the prized cargo. The tree was shipped in small logs from Central America to New York. From there, it was sent to nearby dye factors to be chipped and processed, before being shipped across the Atlantic to Europe.

While logwood dye was highly coveted in colonial America and Europe, laborers and enslaved peoples conscripted to log the trees worked in punishing conditions. Logwood grows in swampy habitats, difficult to settle and navigate. These swamps, however, also offered refugee for maroon communities who were fleeing enslavement elsewhere in the Caribbean.

Spain’s approach to managing Campeche–small bands of logwood cutters traversing the swamps to fell trees–prompted the British to develop what became private property laws, rooted in the concept that a land’s rightful owner was he who most fully cultivated a landscape and bent its peoples to his will. In 1674, as war with Spain loomed, King Charles II convened his Council for Foreign Plantations (which included John Locke) to discuss Campeche, which — along with the profits from logwood — was geographically key to British colonial expansion in the Americas.

Hand coloured copperplate engraving from a botanical illustration by James Sowerby from William Woodville and Sir William Jackson Hooker's Medical Botany , 1810.

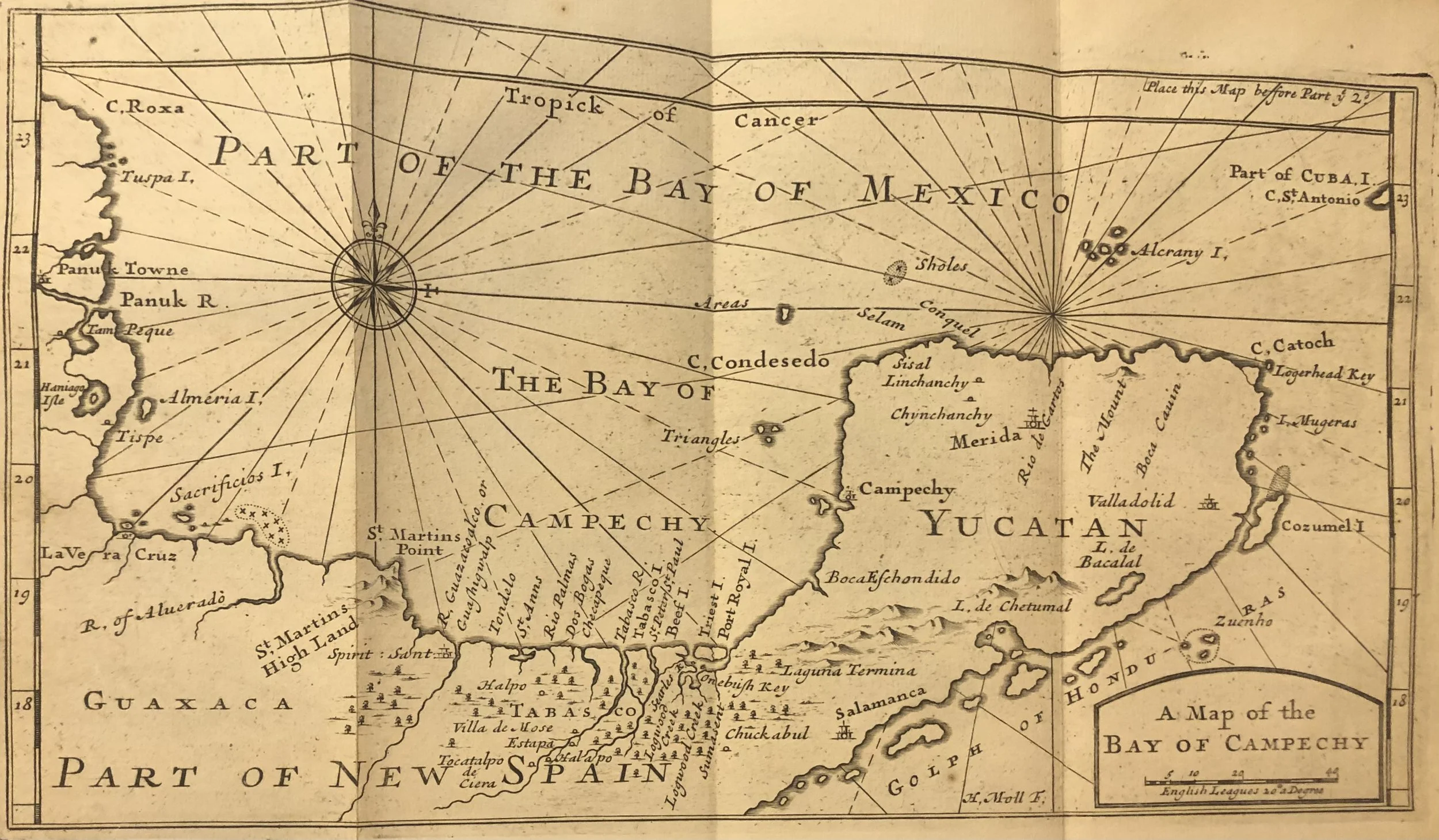

Frontispiece map of Bay of Campechy from William Dampier's voyages; consisting of a New voyage round the world, a Supplement to the Voyage round the world, Two voyages to Campeachy, a Discourse of winds, a Voyage to New Holland, and a Vindication, in answer to the Chimerical relation of William Funnell, 1705. New York Historical Society.

A Map of A Part of Yucatan or of that Part of the Eastern Shore within the Bay of Honduras Alloted to Great Britian for the Cutting, 1786. New York Historical Society Archives.

Charles sought a legal rational to force Spain’s hand, forestalling war and laying rightful claim to Campeche. The Crown’s aims were aided by domestic precedents in which land held in common had been re-classified as “waste land” and so available for seizure and conversion into private property. The Council for Foreign Plantations, in writing drafted by Locke, transposed these domestic policies to oversees colonial lands, arguing that Spain’s sovereignty claims were void, as they had failed to cultivate Campeche, leaving it as so much waste. These doctrines of land seizure, rooted in logwood’s ecology, served as an important precedent for the development of modern private property laws.

While logwood’s popularity as a dye declined by the late 1800s, it remains the only suitable cell dye, and was instrumental to the development of microscopic technology, genetic science, and histopathology (the study of diseased cells and tissue).

For all that logwood is now largely forgotten, the profits made from it funded Empires, cities, and family fortunes, leaving enslaved communities, ecological destruction, and armed conflict in its wake. Logwood embodied the violences of colonial ventures, while also, through its properties, resisting or eliding complete subsumption: the fugitive quality of its dye, its swampy ecology.

—AB Brown and Gwyneth Shanks

An 1892 period drawing of the New York and Boston Dyewood factory in Boston. Schooners, shown moored, were used to bring the logwood from Central America. Drawing from A Tale of Two Trees - Logwood and Quebracho 1798-1948 by J.E. Stevens JE, published in 1948 by the American Dyewood Company.