a haunted botany: a performance for a forgotten forest

Maine Maritime Museum, Bath, ME May 17, 2025 Cloudy, light rain with temperature of 57 °F

a haunted botany: a performance for a forgotten forest focused on Eastern White Pine, an evergreen that once grew as large as Sequoias throughout the Northeast. It was originally used by the Wabanaki as a medicine, food source, building material, and as the inspiration for creation myths. Also known as “The Tree of Peace” by the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, the Eastern White Pine was the founding symbol unifying the Mohawks, Oneidas, Onondagas, Cayugas, and Senecas as early as 1142.

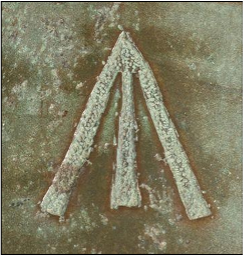

In the 1600s, European colonists began prospecting along the eastern seaboard, and their journals describe the size and abundance of the region’s trees. In 1691, King William III decreed all Eastern White Pine to be the property of the Crown, marking all trees larger than 24” in diameter with the “King’s Broad Arrow” to be used as masts for the British Royal Navy. The Crown’s claims on pine ignited the ire of colonists, fomenting the Mast Tree Riot of 1734 and the Pine Tree Riot in 1772, early precursors to the Boston Tea Party.

The Maine Maritime Museum in Bath is the historic center of Maine’s wooden ship building industry. The Museum’s grounds include the original Percy & Small Shipyard, the only intact shipyard site in the United States that built large wooden sailing vessels. Founded in 1894, the shipyard postdates the height of Eastern White Pine logging in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, but it still primarily depended on the trees, floated down the Kennebec River from upstate, for its ships.

The performance began with a procession along the Kennebec, one of two primary waterways that bisect the state. The walk served as a geographic palimpsest, linking extant landmarks and features in the landscape to Eastern White Pine’s role in the nation’s founding, its industries, and its violences. The performance itself lasted almost two hours due to the overcast and misty conditions. On one side of the sail, drawing on imagery of the Pine Tree flag, the arrangement of archival facsimiles and objects attested to three of the primary threads of the tree’s use: logging, militarism, and nationalism. On the other side, the many objects and archival images were replaced with Eastern White Pine boughs, recentering the autonomy of the tree itself.

Near the end of the performance, performers approached each audience member and placed a handful of pine needles in their hands, inviting them to place the needles in a mortar, to be ground with a pestle, releasing the needles’ healing aroma and essential oils.

Collaborators

Performed by mayfield brooks, AB Brown, Yanira Castro, Galle, zavé martohardjono, Gwyneth Shanks, and Xinyi Zhang

Costumes by James Gibbel

Program by AB Brown & Gwyneth Shanks

Photography by Kari Herer

Videography by Ezra Rose

Sail Fabrication by Doyle Sail Loft

Research Assistant Opal O’Rourke

Produced by Sarah Timm

Funding provided by the Colby College Performance, Theatre, and Dance Department, Provost Office, Center for Art and Humanties, and the Buck Lab for Climate and Environment.

“The world of today runs on oil. In the 1600s it ran on wood.”

—Samuel F. Manning

Histories

Eastern White Pine, or Pinus

strobus, was once the most populous tree in New England, growing as large as Sequoias in the West. The tree has long been used by Indigenous people in the region for medicine and shelter and the Haudenosaunee chose the tree as the central symbol for their multinational confederation, calling it the “Tree of Peace.” The tree’s large, knot-free, and straight trunks made it an ideal candidate for ship building, which resulted in the destruction of all but .03% of old growth forests in Maine alone.

The tree’s long grain and soft, resin-retaining wood allows it to grow straight and makes it supple, lightweight, and durable: perfect for mast building. Its large diameter also means that many trunks could be used directly as masts, foregoing the need to create “made masts,” a more laborious process in which a mast was composed of multiple pieces of wood puzzled together. The tree was imported to England in the early 1600’s by George Weymouth, a colonist and shipbuilder. However, these imported new growth trees were susceptible to disease.

Because of this, old growth pines became economically pivotal to the Crown, fueling war, resistance, and new shipping technologies, including special barge-like vessels to ship these huge trees to England. The British Royal Navy relied on mast trees throughout the 17th and 18th centuries during the Wars of Empire. As Andrew Vietze writes, “navies rose or fell with the ability of home dockyards to fit or replace masts that would stand the crushing force of sail carried in storm or in battle.” King William III enlisted agents to mark particularly large trees throughout New England, as a means of reserving them for the British Royal Navy.

Pinus strobus, collected in Mexico by A. Johnson, 1950 © President and Fellows of Harvard College. Arnold Arboretum Archives (note: photograph behind performance description).

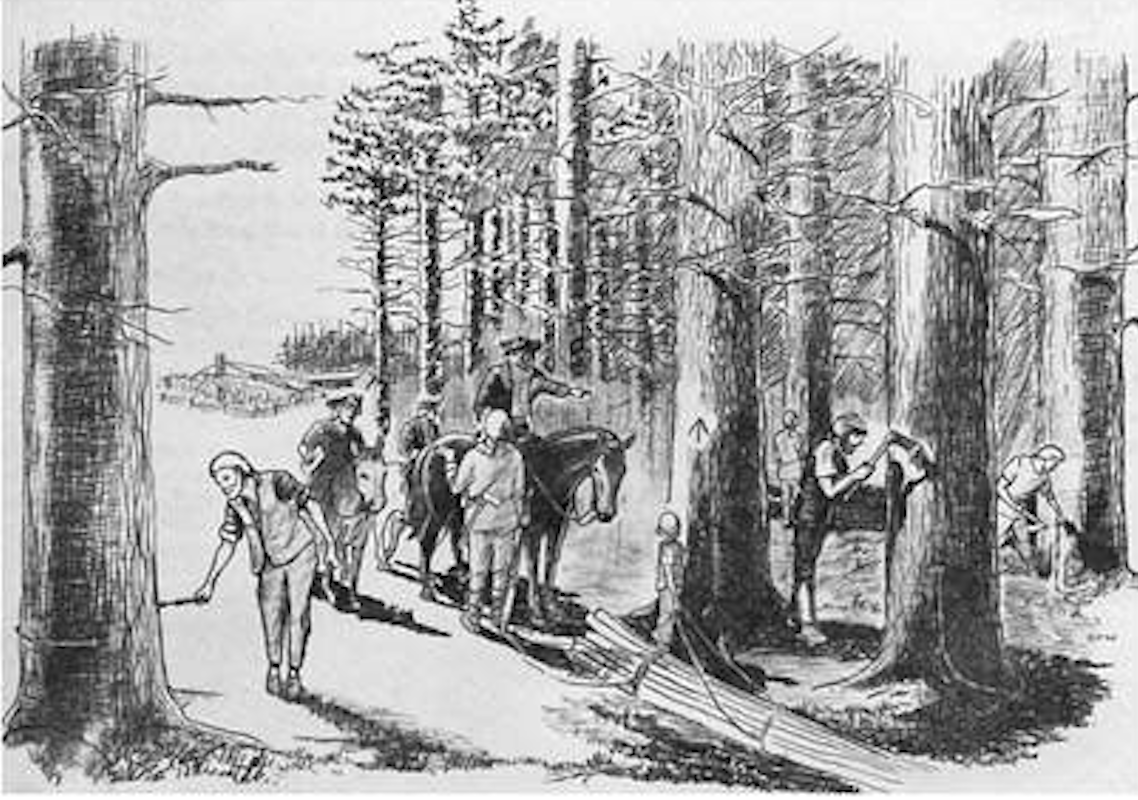

A timber surveyor and his crew cutting the King’s Broad Arrow mark into large Eastern White Pine trees, marking them to be reserved for the British Royal Navy. Illustration by Samuel F. Manning, New England Masts and the King’s Broad Arrow.

By the early 1700s, roughly 200 masts and millions of feet of processed boards and raw timber were being shipped each year from what are now New Hampshire and Maine to England. These old growth trees commanded $25,000 in today’s dollars. By the end of the eighteenth century, over 4,500 masts had been shipped to England.

England’s claims to Eastern White Pine did not go unacknowledged by American colonists. Jockeying over claims to the trees led to the Mast Tree Riot of 1734 and the Pine Tree Riot in 1772, direct precursors to the Boston Tea Party in 1773. The Eastern White Pine became a key symbol for settler identity and lent the moral authority of claims to self-determination to colonists’ occupation and extraction of the natural world.

In 1775, Colonel Joseph Reed, tasked with designing a flag for the newly formed army, asked General Washington, “What do you think of a flag with a white ground, a tree in the middle, the motto ‘Appeal to Heaven’?” The Massachusetts Minutemen adopted this flag and carried it into the Battle of Bunker Hill. Reed drew inspiration from John Locke’s quote, “And where the body of the people, or any single man, is deprived of their right, or is under the exercise of a power without right, and have no appeal on earth, then they have a liberty to appeal to heaven…till they have recovered the native Right of their Ancestors” (Second Treatise of Government). In recent years, the so-called “Appeal to Heaven” flag was carried during the January 6 riots, enlisted to serve right-wing and white supremacist ideologies invoking the “Right of their Ancestors.”

Illustration from 1912 Chase & Sanborn Coffee American Flag Advertising Booklet

John Trumbull, The Battle of Bunker's Hill, June 17, 1775, 1786. Oil on canvas, 25 5/8 × 37 5/8 in. Yale University Art Gallery.

The flag was a presence at the Jan. 6 attack on the US capitol. NYT/Associated Press.

Concerns over Eastern White Pine’s deforestation, one of the first trees to undergo such extreme logging in the US, helped launch the modern conservation movement in the US, shaped by figures like Henry David Thoreau, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Theodore Roosevelt, George Perkins Marsh, and Gifford Pinchot. Pinchot, the founder of the US Forest Service in 1905, was heavily influenced by the mid-nineteenth century writings of Thoreau, whose famous The Maine Woods (1864) was an attempt to document his failed quest to visit old growth Eastern White Pine, and Marsh’s Man and Nature (1864), a “clarion call for all nations to end the devastation of the land,” inspired by close observation of logged Eastern White Pine forests (John Pastor, White Pine). Beyond encountering these texts as a young man, though, Pinchot grew up with the painting Twilight, Hunter Mountain by the Hudson River School painter, Sanford Gifford hanging in his living room. Pinchot’s father had made his fortune through logging, but later in life “realized a conversion to conservation” (Pastor). Gifford’s painting, the young Pinchot’s namesake, depicts a logged forest, only stumps remaining, as the sun slowly sets.

The Eastern White Pine tells a circular history, recording not only its age in growth rings, but also weather conditions and ecological change over time, and bears witness to the destructive forces of extractive industries. Ships built with Eastern White Pine masts propelled wars at sea, the Triangle Trade, and the devastating whaling industry. At the same time, dead snags persist in old growth stands, and these downed trees or stumps are often older than the oldest living trees; “altogether, these generations of white pines may span a thousand years or more” (Pastor). Just as the tree reappears after the Ice Age or again on the flag of anti-democratic and authoritarian riots, it teaches us about the connection between the past and the present, and about survival amidst our current moment of ecological collapse and rising fascism.

—AB Brown and Gwyneth Shanks

Sanford Robinson Gifford, Twilight, Hunter Mountain, 1866. Oil on canvas, 30 5/8 x 54 1/8 in. Terra Foundation for American Art.